Wednesday, December 12, 2012

"A Word from the World"

I wrote this story years and years ago. Then it was part of a novel that drifted away. It was published in an anthology called "Winter Tales" in more or less the same form as you have it here. I posted it a year ago but I wanted to put it back up because I have a lot of affection for it and I recently aired my reading of the story on episode 49 of "Tales to Terrify." Except for my father not being killed in World War II, it's almost autobiographical. Here it is. It's called...

A WORD FROM THE WORLD

The snow had started the day before. The sun was bright in a clear sky and it snowed! Each flake caught the sun. Sparkles swam in the air living along the wind. People passing on Cottage Street looked up to the clear air to let the cold colors hit them in the eye, or on the glasses. They smiled, admiring their shadows as they walked and the sunny, sunny snowstorm falling around them.

A genuine curiosity, Pop-pop called it.

Soon, though, the sky became gray and the snow continued into the dark. This was more like it. All that blew and rolled down streets, all the things that stood at corners, squatted in the back alley or at the bottom of the yard were, first, stopped, then pinned to the ground by the falling snow, then covered into smooth lumps.

It snowed all through supper and after. It snowed through the radio and Pop-pop's reading. It snowed even harder when I went to bed. All night, I'd wake and go to the window to wish for more; I pressed my face against the cold glass to peer at the sky above the eaves. I wanted there to be more snow in it. And there was. The sky was black but the air was lit by the streetlight at the end of the alley. Pieces of white day fell through the night and brushed little whiskers against the glass. I thought the wet chill would crack my cheek when I smiled.

In the morning the world was new. Yesterday's lumps were smooth and the spaces between them were even and white. In the yard, the snow had rolled in on waves of wind from over the far fence and dropped quietly and deeply. It filled the space from the back of the house to the alley, then buried the fence and the alley. Then it buried the Erby's fence across the way; then buried their yard, too. Then everything was all the same.

When the wind blew hard enough to make the electric pole by the corner sway and the wires clack and chatter their icy silver loads that had been building through the storm, Pop-pop looked up and down the alley. He shook his head. "We'd best stay in," he said. "All of us." Falling wires, he said. Careful, he said. Electrocution, he said.

Nanna looked into the pantry and shook her head. "The food'll never last," she said.

When the wind howled, the snow rose alive, spinning, and the world went white. So big a thing as Mount Amos disappeared. So too, did Aunt and Uncle Erby's house across the alley. Our yard began, now, at the back door and went on forever, around other houses and on forever. The world was just our place, just our house and the sweetly shaped mounds of snow stretching forever. A few black lines crossed above, or rose from it. A pole down the way. The very tips of the back fence, dead black morning glory vines still hanging in tatters from summer. Then nothing. The end of the world. Our place only.

I said once that by the time the telegram came, I already knew. Here's what happened.

It was in that snow. Mother and I were on the front porch. A trolley passed the house and rumbled slowly, slipping, wheels spinning uphill toward the end of town. A man came up the sidewalk. Through the snow I heard him whistling Rum and Coca-Cola. I laughed. Snow was blowing in front, behind, around him. It was climbing his legs and wrapping his face. It looked as if you could see right through him, as though pieces of him were being carved away by the wind. He looked alive inside with snow.

I laughed some more. He heard me laugh and looked up. He saw me on the porch with Mother. He looked at the door behind me then at the envelope in his hand. I laughed and he had seen us. Mother was tucking me, buttoning my face into the wool snow suit, already wet from the blowing snow. I laughed and she turned to see. She saw the man coming and stopped, her fingers stopped on the button at my mouth. I could smell cold, wet wool and my mother's warm skin, cold cream smooth and fragrant from morning's dishes.

The street was empty. The hill was white all the way to where it disappeared. Black sticks stuck out, here, there: Trees. A fence. Phone poles. The trolley tracks were black lines along the way, then they glazed over white, then vanished. The wind howled and for a minute the street faded into white, then vanished, too. The man disappeared with the rest of the world. The world was our porch and Mother frozen at my mouth and I thought, "Good. He's gone. Daddy'll be alright." Then the wind dropped its voice, and the man stepped onto our porch and shook his hat like a dog.

There was nothing to it at all. He wiped his glasses with his finger like a windshield wiper. They fogged up again and he took them off and squinted at the paper.

"Mrs. Er-ness-toe De Angel...?"

Mother nodded. "DeAngelo, yes.††Ernest. It's just Ernie. His name is. Yes. Ernesto. But he's just Ernie."

He brushed the snow off the envelope, gently. He was so gentle; she reached for it, took it, held it, turned it over in her hands. He said, "sign here," and gave her a book and a pen. It wouldn't write.

"Sorry," she said. He took back the pen and blew on it, then rolled it between his two hands, shook it. A big splat of blue plopped onto the snow on the porch. "Sorry," he said. She said, "That's alright." and wrote in the man's book. She put the cap back on the pen and handed it to him, said, "I'll have to get you some money..." and he, "That's okay, Mrs. ma'am. That's okay. I don't need any. I don't usually get." Then he was gone toward town. Another blast of wind rolled the snow, but I could still see him. In a second, the trolley loomed down the hill. It slid on the rails. Sparks showered into the snow from the line above. It stopped. Silent for a moment. It was the only thing we could see in the world. And the man. The trolley and the man. The man got into the trolley. The bell clanged and sounded very close in the wooly snow and the silence. The sweep of the wind went with it, somehow. The trolley growled its sandy wheels against the tracks and disappeared toward town.

Mother held the envelope. I had been forgotten. The wooly button at my mouth was still loose. The envelope was very small.

I knew it meant that daddy wouldn't be home; that he was going to stay at the Pacific Theater. Until the next show. Or the next one. Can you imagine that? That he'd stay away for a long, long time and that I'd be an orphan, now. I didn't want people to look at me right then. I didn't want them to talk to me. All I knew was the backyard was filled with snow taller than me.

I followed her into the house. I was a ghost. Invisible, I could make noises but not lift things, not change things. I could only be what had already been.

No one spoke. Mother stood in the living room and looked at the envelope. It dripped. Nanna came down from upstairs and stopped on the steps to look. Pop-pop came in from the kitchen and looked. I continued on through the house. No one noticed. To the kitchen. There were voices, distant, behind me. I went out back. I was ready for the snow, for the day. The whole expanse of the yard was at my feet. The snow drifted in curving hills to the second floor of Uncle Erby's place. Maggie the dog, looked out an upper window at me. Her tongue on the glass made clear places in the breath haze that bloomed around her nose and muzzle.

The snow started at my feet. I could tunnel through the world, I thought. A tunnel could go anywhere. Everywhere. It would be very cold under the snow, but maybe not too dark. Snow was white.

I dragged open the door to the back porch toilet, the kaibo Pop-pop called it. It was now just a storage place for garden things, junk, old spiders and must, things forgotten. My summer shovel and pail. Too small to dig a tunnel through the world. I tossed them aside. I found Nanna's garden spade. Too long. Too heavy. Pop-pop's cinder shovel was just my size. He used it to fill gunny sacks with furnace ashes. These he kept in the trunk of the LaSalle for winter weight, for traction. The shovel was short. Light. It had a pointed blade. I could dig anywhere with it. A good tool is the first part of a good job, Daddy'd said.

I scooped as I waded down the steps. I tossed, packed, shoved and soon was at the bottom of the porch stairs. The snow rose over my head. I was surrounded by whiteness and was dripping hot already. Sweat tickled down my back and became cold on my skin. I pushed my mittens into the snow in front. It gave way. I leaned into it and fell, slowly, gently carried to the ground. I scooped shovelsful behind me. Soon I was on my knees and burrowing like a groundhog on my way. I shoved the cold, packed whiteness aside, pressing it against the walls of my tunnel. Forcing my way into the heart of winter. It was bright day.

I realized soon how large the world was. I had no idea before. I scooped and scraped, patted and pressed the sides of the tunnel, the roof, smoothed it all, made it nice. Kept going. The sun was far away, on the other side of the snow roof. Out there.

Faint light seeped from where I had begun at the porch, down to where I dug. It darkened as I scooped. I wished I had brought daddy's nightcrawler lantern. I could see it under his bench in the basement. I could see it in the cardboard box, a rag covering most of it. I could see its little clear dome and shiny handle, its flat metal base. I could feel its weight, carrying it. In the darkening snow tunnel, I could almost see the rings of light it made on the tree leaves overhead, could almost hear daddy talking about the fishing we'd have with this beauty that he dangled in my nose before dropping it wriggling into the pail, laughing. Mosquitos and other sweaty summer bugs sang in my ears, climbed in the light against the leaves. The fat worm wriggled into the dirt in the pail and was gone.

The lamp was back there, a world away. In the basement, under the place where people talked.

My breath was just dull gray, now, not silver bright anymore. I wondered how far I'd come. Nowhere near the other side of the world, I knew that. I didn't think I was even at the end of the yard. I tucked my knees to my chin and scooted 'round to lean against the tunnel wall and breathe. The Erby house was ahead. I'd have to get around it. That was first. Then around their garage. Then through Pan's Park. Then up the mountain. After the mountain was the other side, down to Carsonia. A long way from there was Philly. After that, I wasn't sure. I knew that the Pacific Theater started somewhere after Philly. Daddy had gone first to Philly. Then somewhere else.

If I could only remember what Daddy had said. About everything. I could find him, if I could remember. I knew that. Everything that Daddy had said was important, now. Was clues. I had to remember to not get confused with other things. Things I made up, things other people told me. If I could remember it all, I could get to him and we could watch Gone With the Wind together at the Pacific Theater, then come home. Maybe get some ice cream first at Rexall, some hot chocolate. Then we'd come home. I was really mad. Just like daddy got sometimes at me. I was really mad!

When I punched the sides of the tunnel, the wall gave way a little. I punched it again, then I scooped. I widened the scoop. I scraped above, dug below. Soon there was a side passage going a different way. It pointed toward 18th Street. I knew that. The world was so large. I could avoid the Erby house, go around it, then up, up, up the mountain. I started deepening this new route. It was very, very dark in a very short time. Black. I had to back out to where I had branched off. Maybe the other way. I dug for another few minutes until it got too dark in that way and returned to the main shaft.

A curve? Maybe the light would follow a gentle bend? It seemed right and I started to angle left, making the main route to the world into a long gentle arc. Soon it was dark again and I just wanted to stretch out and rest. I was going to need light. I scooped out a little room in the snow, enough space for me to just stretch out. I lay flat on my back. Looked up. If I closed my eyes and pressed against them with my mittens, it was a different dark than if I kept them open. I liked that. It was so quiet out here in the world. The snow was just a few inches above my face. I reached up and smoothed it. Smoothed it flat. Smoothed it hard like a well-packed snowball. It was warmer in there than it was on the outside where wind blew and the cold tried to suck the air out of my chest. There was no wind and the tips of my ears were hot. My fingers were wrinkled. It was warm. I made a little place to lean. It fit me well and was so comfortable. I scraped the ceiling. Some snow fell in my face. It tasted good. Almost sweet. It melted in my mouth and trickled down my throat. It melted on my nose and ran down my neck.

How long would the snow last? How long until it went away and the whole earth would be hard and confusing again with too many roads everywhere and not enough ways to get there? Snow always lasted a long time, but never long enough. I couldn't really rest if I was going to tunnel to the Pacific to find Daddy. I started again. Didn't think, just started into the darkness.

That is what I'm doing, I said. I'm digging to find Daddy at the Pacific Theater and watch Gone With the Wind with him, Sock, the Morons, the First Shirt and all the guys from basic training and his letters. We'd all be together. Maybe I'd need an airplane to fly over the boot camp, to fly over England where the drooling British lived in darkness, and to get to the Pacific Theater where they were all watching Gone With the Wind. I knew it was a long way to travel. But all the world was covered in snow. I was certain of that and that meant that I could get there from here. I'd dig under boot camp, under the British. Then I'll bring him home and we can all go to Carsonia Park and this time, THIS time, I will, I will ride Blitzen the Roller Coaster and maybe I'll even stand and not worry about the "Don't Stand" sign. I'll forget about rats and dirty feet. We'll go to the shooting gallery and shoot the bear together and win big rabbits and give them to Mother. I won't loose my shirt, I won't loose my head.

I was digging in the dark as I was thinking. It was pitch black. I couldn't see anything. I could just feel the snow, the cool snow giving way and being left behind. I hit something. It was hard. It was not ground, not snow. I scraped away around it. It was wood. I could feel it. Wood. It was smooth. I recognized its feel. It was an edge, the edge of my sandbox. I had dug to the sandbox. I was only to the sandbox. On it, had I been able to see, would be puppies playing with butterflies. A boy and a girl digging in the sand by a beach. Waves would be rolling, painted on the wood of my sandbox. I was only to the box and days must have gone by since I started. I scooped around the edge of the box, opened up the tunnel to another direction. I was angry, yelling, was only to the sandbox. I stopped and leaned against the wood. It felt warm. Summer was still in it. The plywood top covered the sand. The sand was summer. It was still there. Still in the box under the snow with me. It was summer and back when I had a daddy.

I could hear my breath coming in and going out. I couldn't see it. Soon I got quieter. It was warmer. I heard nothing. No breathing. No. No wind. Nothing at all. Not Carsonia. Just the distant voices of memory.

My tunnel dropped away; it fell behind me. I was lifted from the world into a swirl of snow and the blasts of wind; there were arms all around me. There were legs and chests, Pop-pop's jowls and Mother. Her hands took me. Hands carried me to the house. It was hot. I was laid on the table. The light was overhead. Bright. I felt hands reaching, opening my snowsuit, hands reaching into the wet wool and drawing me out, peeling my clothes away. Then, I was bare and was being carried up the steps. Water was running in the tub. Mother's hands rubbed me. Nanna's voice said rub him with a terrycloth towel. Rub him and here, make him drink this shot of liquor. And burning hot, it went down my throat and sat warm in my stomach. I wanted to and I did throw up. Then I went into the hot, hot water and everything was steam, and water lapping in my ears. And there were tears.

Later, Mother told me, in bed, that Daddy was lost in action in the Pacific Theater. I knew that. But I listened to her anyway.

I wondered for days after if I had died. Of course I had not. Dr. Kotzen said I was fine. Pop-pop looked for his shovel for a long time. I kept thinking it was in the Pacific. When the snow was gone, there it was.

Thursday, October 25, 2012

"Tale-Telling"

Were you read-to when you were a tot? Do you remember getting something from a story the adults never dreamed was in there?

Harry Markov, my co-editor at Tales to Terrify, has set up a blog tour that will take us through Halloween. The goal of this 'tour' is to introduce people to "Tales to Terrify" AND to sell copies of the book...THE Book, "Tales to Terrify, Volume 1" -- the which is due out on -- you got it -- Halloween.

Take a look...Here's the most recent blog: http://sqt-fantasy-sci-fi-girl.blogspot.com/2012/10/tale-telling-by-lawrence-santoro-tales.html

And here is my tale...

TALE-TELLING

If you’re a listener to Tales to Terrify on the District of Wonders Network, you’ve heard the first part of this story. My grandfather, Pop-pop, read to me when I was a kid; he perched me on his lap and read stories, poems, whatever. Not kid stuff, he was a high-octane reader of dark things, things by Lord Byron, Stevenson, the occasional Lovecraft piece, others. He was particularly fond of Poe and, until I learned better, poetry was so-called because those rhyming tales were written by Edgar Allan Poe.

Earlier though—and this may have been the first tale he told to me—he read, “The Midnight Ride of Paul Revere.” “Listen, my children and you shall hear/Of the Midnight Ride of Paul Revere…” that one?

Longfellow’s simple patriotic piece scared the pants off me and did so not only as it was being told, but the images it raised followed me into sleep and into the morning and through the light of day.

Take a look. Imagine this, steeped in a three-year-old’s ignorance, about our hero’s friend who…

“…climbed the tower of the Old North Church

By the wooden stairs, with stealthy tread,

To the belfry chamber overhead,

And startled the pigeons from their perch

On the somber rafters, that ‘round him made

Masses and moving shapes of shade,

--By the trembling ladder, steep and tall,

To the highest window in the wall,

Where he paused to listen and look down

A moment on the roofs of the town

And the moonlight flowing over all…”

“Stealthy tread…belfry chamber…somber rafters…trembling ladder…moonlight flowing over all.” Imagine this as read by an old man whose glasses glowed in the porch light as crickets chirped their metallic calls and perhaps some lightning, which may have flickered over the mountain; not even to mention, the muffled oars as Paul Revere rows past the British ship in the harbor—“a phantom ship…a huge black hulk magnified/by its own reflection in the tide,” and other things of dark and night…

Well, in my head, the British are not just soldiers of a king; to three year-old me they are that which IS the darkness, creatures who swarm like shadows from this vast black hulk in the bay and march with ominous tread across the world.

As pictured, they bigger than Pop-pop or daddy, larger even than uncle Jim. They were hulking shadow with fangs and a stench of rotted meat (why that? I don’t know but once, I smelled some hamburger that had gone off in the back of our fridge and made a stink as rotten as any monster, so…). And, they grunted in the thousands as they trod the streets of the town. Our town. Of course.

In the poem, Revere rides the night, rouses the country folk and the story is over and I’m put to sleep. And still, I hear the tread of the British and see the sparks struck as Revere’s horse flies before the wind into the countryside to wake every Middlesex, village and farm and I know those sparks will breed a fire that will burn to light the night and then…

…and then I’d sleep. And sleep embraced my fears, drew them closer, turned them to dreams from which day delivered me. And even then, I’d hurry past the side hall outside my room, the dark passage that led to the darker attic where I knew they waited, those British did. And, most important, were kept in place because I knew them there. Ha!

Next story time, I’d ask for the “British one” from Pop-pop. He’d ask, “British? What story’s that?” And I’d say, “Listen my children and you shall hear.” And maybe he’d read it again. And I’d run back to the dark, past the side hall, to meet them, and the other holy terrors of tale-telling, in my dreams again where, again, they were defeated.

Later, of course, the “British” became just people, a disappointment that survived.

Still, to this day, I carry inside me two versions of “the British.” In one, they are just dwellers in a lovely land in which once I lived. The other? You know what they are.

So, thank you Pop-pop. See? It’s not just the story, it’s the story-telling that I hope we bring to “Tales to Terrify.” And I hope you’ll become regular listeners. I hope too you’ll consider picking up a copy of “Tales to Terrify, Volume 1” when it comes out this Halloween.

May they all breed pleasant dreams.

Wednesday, October 17, 2012

I NEVER DRESS FOR HALLOWEEN

I haven't dressed for it in damn near half a century. I annoy friends, show up at their costume parties as, "what the hell’s he supposed to be?"

"Ah…a depressed writer?

See? To me, Halloween smells like mothballs.

Every year the first whiff of apple cider or the whisk of dry leaves waded-through or wind-drifted against whatever door I live behind at the time starts it. But in deepest October, parties, leaves and cinnamon-cider aside, I catch a scent of phantom camphor in my life and feel a dry wool ghost brush my bare skin. And there I am: in the attic at 831 North Fourth Street, Reading, Pennsylvania, delving for Halloween.

831 was built at the turn of the old century. It’s nothing special. Like most houses in that railroad town, it was red brick with a slate roof. Bigger than most, older than the shotgun row-homes on the half-streets where my friends lived. And 831 had a fake Tudor half-beam attic above the second floor.

It was a scary place in which to be young and invent your world. My best friend, Pete Reinhart lived up the way and across from Charles Evans cemetery. He bragged about guts, living near the dead and all.

Not much to be afraid of. Evans was a rolling green forest, dark mossy trees and brown hills going to seed. It was filled with soot black mausoleums, tall granite memorials and the iron-spiked flags of the war-dead. In summer, Evans was a great place to pack lunch and go read, leaning against cool granite in shaded heat. In winter it had the best sledding hills in the northwest corner of the city.

No, 831 was scarier than Pete’s graveyard neighbor. Our place had a house-long cellar lit by three hanging bulbs with and a wooden coal bin the size of New Jersey at the front. When we moved in, Fall of 1947, 831 had a gas-fired water-heating 'coil'. The thing had to be lit and extinguished manually; turn the cock, listen for the his, strike a spark and hope it didn’t blow.

In the cellar’s near-dark, the coil flickered, hissing just beyond the octopus-arms of the furnace. The damn water heater waited to kill. You never went out–not to a movie, not anywhere—and left the coil on. A constant check went back and forth, mother to daddy, daddy to me, me to Pop-pop, "you turn the coil off?” “Did YOU?” “You turned it off, right?"

The coil--and shining black water bugs, mice, smells of mold and rot and noise s not accounted for, and bad bad darkness, all that was below.

On the living floors, the house whispered constantly. Walking from room to room, boards cracked in places where feet were not. Alone afternoons, distant rooms sighed. Small things chattered in the walls.

Gas jets, capped and dead, covered softly with decades of paint, poked from the same walls where, from time to time, zillion legged critters coiled forth and oozed down to disappear into the baseboards. Hallway chandeliers shivered and clattered in the stillest air. Several parts of the house had external wires ending in big rotary switches that showed bare copper. Daddy always said these circuits were cut from the mains—he did it himself, damn it.

Mother nevertheless always stopped, perked, listened, entering these rooms, alert to faint crackles of electricity from those dead lines.

Finally, daddy ripped the damn things off the walls and plastered the holes. There!

(Halloween, Larry, get back to Halloween)

Halloween began in the attic. The attic was up the stairway at the end of a dark second-floor side-hall, a place dad never re-electrified and which remained, consequently, always in ambient dark. At the top of the attic steps, a wide, mullioned window overlooked our yard, the back alley, the yards of my friends Davey Brown -- a Seventh Day Adventist always somewhat depressed because the world was ending soon -- and Terry Hebhardt -- who did shitty things because he was going to get beat up for something he did or didn’t do, anyway. My world. Beyond, lay the rest of Reading, red brick and slate. A mile further, the town tipped upward till it washed like a breaking wave against the green slopes of Mount Penn.

In October, the mountain was red and yellow.

The steps to the attic were always dusty. The walls of the hallway and stairs were runneled and rough, its wallpaper bearing medieval tapist scenes of stag hounds. Huntsmen on rearing horses, their pikes angled in a forest of passionate tangles, worried a deer. Old stuff, dark with blood.

In the attic, everything creaked. The floor boards were splintery soft woods, ages of dust packed between. With even my modest weight the floors sagged. The ancient cabinets and stored furniture nodded or quivered as I passed. Nail heads squeaked slowly up from the wide floor planks like thunderstorm worms that peered up from damp garden earth. No place for bare feet, our attic.

The front windows overlooking Fourth Street were large and mullioned. The branches of the elm canopy reached from the curb to the windows, their fingers tapped them in the wind. There always was wind and the room always was shaded by branches and gathered dust.

The smaller attic room was darker. It looked across the narrow way between our house and Cliffy Mahler’s. Into Cliffy's bedroom.

This room was filled with time. Stacked trophies of my Pop-pop's long run as a national skeet shooting champion. There were piles of books from his, Nanna’s, Pop-pop’s kidhood. There were my mother’s boxes filled with fading, dying pictures of long dead people and the scent of sachet and newsprint. And there were trunks: steamer trunks of wood and leather panels, brass corners and varnished hardwood ribs. Footlockers with more hinges than necessary, multiple straps and a dozen snaps; there were wooden crates, valises, satchels whose leather was flaking into dust from times before I was born, from the time when my parents had been "on the road!"

Their life on the road was piled in the corner, one box, valise, trunk, and case atop another.

You've come this far with me. There's something you should know. My parents were dancers, members of the Catherine Behney Dance Company. Don’t rack your brains, you've never heard of it before now. Behney’s was one of many companies supported by Franklin D. Roosevelt's Federal Arts Administration projects during the Depression. After the New Deal died, the company became part of a traveling carnival. My father, Rocco Vitorio Santoro, was a guy who slipped away from home at 13 to earn his own damn way in the world. He worked a couple years at Mother Hubbard's Candy Company, 60 miles from home, then got a job driving truck and setting up for the Behney troupe. Trainable, he joined the corps. Eventually, when Behney joined the carnival, he earned a few extra bucks as a wing-walker, days, working with a barnstorming pilot who toured with the show. When someone was injured or too drunk to compete, daddy also filled in as a miniature racecar driver. Just as needed, you know. In addition, he met his future wife, Fern Emma Adams on the road.

Mother was the troupe's prima ballerina. She also was a poet who never wrote, a painter who didn't paint, a runaway rich kid, who fled Princeton and West Point weekends and who had given up on her own schooling a couple weeks shy of the end of her senior year in high school. She was a sweet girl who ran to the road from her mom and dad -- the social crème of Reading and Wyomissing, PA . On that road, she fell in improbable, wonderful, madly focused love with this grade-school dropout son of immigrants who, every couple days, wired himself to the top wing of a Steerman biplane and stood out there for inside loops, outside loops, and

Immelmen turns, who danced some and ate bugs and streaming dirt for the crowd's thrills and the few extra bucks it brought.

On the back-leg of a southern swing into deep Florida, they married in D.C.

The trunks in the attic room at 831 North Fourth were filled with their road years, the parts they brought home when they settled in Reading to become the boring guy,

the pleasant housewife they disguised themselves as for me.

Those trunks were Halloween.

Opening each lid sucked the air of their years on the road from the bottoms, from between folds of cloth, from the sleeves, legs and necks of clothes, costumes and apparatus, jackets, boots, leather helmets, furs and goggles, silks and makeup, hats, feathers, powders, greasepaint and stays, elastic and crinoline, crepe hair and dry sponges, from below it all, from through the fibers, the air ran picking up dust and essence. And through tubes of camphor crystals and deliquescing mothballs the air picked up the scent I knew as Halloween.

Everything from those boxes and trucks scratched my skin, smelled of age and other places and times and covered me completely, hid me perfectly in what they had been. The costumes we put together in the days before Halloween created a high standard of disguise. Nobody, anywhere, knew me. Not at school before unmasking, or in the back alley, when Dave Brown, Terry Hebhardt, Cliffy Mahler, Pete Reinhart, saw and didn't know me until I spoke and then, “Holy Jeeze, Santoro, that you? Christ!”

The costumes also became something else. Something that should have been obvious to me, but wasn't. Was not until I wrote this did I realize: Halloween put me into their skins. My parent's skins. The skin they'd discarded to build me. Who was I? Dressed as a Scotsman, a World War I ace? A harlequin? Was I them? Dad, mother? Christ, no. Just me...but... Hell, no! They were—they are—my parents.

Christ, don't you have to kill them off to become you?

Sure you do. Christ.

When I stopped having to dress for school Halloween parties, what was it, in seventh grade? I never did again. I forgot the stuff that was left in the attic, then I left home and, several years later, moved to England.

Mother and Daddy with another couple, people I didn't know, were killed driving back from Florida when a guy coming the other way had a heart attack at his wheel, died instantly and his car jumped the median and dead-ended into them. Five gone. Like.

That.

I returned for a few months, got rid of the remnants of their lives and went back to England.

And, no, I do not dress for Halloween and still the season smells of mothballs.

END

COPYRIGHT © 2012 Lawrence Santoro

Friday, July 27, 2012

"Tales to Terrify" is a Parsec Award Finalist

I received word this morning that the podcast I've hosted since January 13 of this year, "Tales to Terrify"by name, has been nominated for a Parsec Award.

Thanks go out to the show's producer Tony C. Smith, co-editor Harry Markov, art director Skeet Scienski, and Tim Ward, who put all the information together for the Parsec committee. And of course thanks to the authors and artists without whom I'd just sit at the mic and mumble about my cat.

The Parsec Awards were founded in 2006 by Mur Lafferty, Michael R. Mennenga and Tracy Hickman. They did so to “celebrate Speculative Fiction Podcasting, under the banner of Farpoint Media.”

The shows are nominated by fans and finalists are chosen by a steering committee. That’s where we are now. We finalists are then voted on by an independent panel of judges from outside of podcasting.

When we began after the first of the year, it was us and our big sister, the Hugo Award-winning StarShipSofa.

Now we are four.

The StarShip and Tales to Terrify have been joined by "Protecting Project Pulp" and "Crime City Central," classic adventure and crime fiction respectively. Taken together, we are "The District of Wonders Network." Stop by at http://districtofwonders.com/

So. On to the rest of the day. There is a new show up right now, one I've wanted to do since the beginning, William Hope Hodgson's "A Voice in the Dark."

Thursday, April 05, 2012

Marting Mundt and Lawrence Santoro Together Again At Long Last

Time for some self-absorbed chestbeating and unabashed bookselling. Martin Mundt and I are doing a two-hour, round-robin, sudden-death reading here in Chicago. I'll be doing nothing but DRINK FOR THE THIRST TO COME. Well maybe a touch of the new novel, A MISSISSIPPI TRAVELER, OR SAM CLEMENS TRIES THE WATER, just to test-fly it. The poster tells all. If you're in Chicago, I hope you'll stop by. And if you do and you haven't picked up a copy of DRINK... please do and if you do and you like it, please go to Amazon.com and give it a glowing review.

Time for some self-absorbed chestbeating and unabashed bookselling. Martin Mundt and I are doing a two-hour, round-robin, sudden-death reading here in Chicago. I'll be doing nothing but DRINK FOR THE THIRST TO COME. Well maybe a touch of the new novel, A MISSISSIPPI TRAVELER, OR SAM CLEMENS TRIES THE WATER, just to test-fly it. The poster tells all. If you're in Chicago, I hope you'll stop by. And if you do and you haven't picked up a copy of DRINK... please do and if you do and you like it, please go to Amazon.com and give it a glowing review.I did say please.

Tuesday, March 27, 2012

TALES TO TERRIFY 'Casts all 6 Stoker Nominated Short Stories

The image is from the publication, "The Uninvited, No. 1" The illustration is for the short story, "Hypergraphia" by Ken Lillie-Paetz, one of this year's nominees for the Horror Writers Association;s Bram Stoker Award for Short Fiction.

The image is from the publication, "The Uninvited, No. 1" The illustration is for the short story, "Hypergraphia" by Ken Lillie-Paetz, one of this year's nominees for the Horror Writers Association;s Bram Stoker Award for Short Fiction.For the past two weeks, the podcast I host, Tales to Terrify, has been 'casting this year's short fiction Stoker nominees. The six stories were...

Well you can go to the site and find out yourselves. Listen to them. They were good... We finished up last Friday with Stephen King's "Herman Wouk Is Still Alive."

For our effort, we had an item in the News section of Stephen King’s website. The notice says:

“Herman Wouk is Still Alive on Tales To Terrify

"March 26th, 2012 1:19:36 pm

"TalesToTerrify.com has posted a podcast that features readings of several nominees for the Bram Stoker Award for Superior Achievement in Short Fiction. Lawrence Santoro provides a fantastic reading of Stephen’s Herman Wouk is Still Alive at the 1 hour and 10 minute mark. Enjoy!

http://talestoterrify.com/tales-to-terrify-no-10-bram-stoker-awards-special-part-2/

As mentioned, we played ALL of the Bram Stoker nominees in the Superior Achievement in Short Fiction category but there we have it.

Hope you'll stop by now and again, and again and again. There are big things coming.

Friday, March 23, 2012

GENE WOLFE AT SANFILIPPO

We'll start with pictures. There are quite a lot. On Saturday, March 17, 2012, the Chicago Literary Hall of Fame gave Gene Wolfe its Fuller Award. The event was held at the Sanfilippo Estate in Barrington, Illinois and drew hundreds of friends, colleagues and fans -- and the lines distinguishing fan from friend from colleague were virtually nonexistent -- from all over the country. Peter Straub, Neil Gaiman...et al.

We'll start with pictures. There are quite a lot. On Saturday, March 17, 2012, the Chicago Literary Hall of Fame gave Gene Wolfe its Fuller Award. The event was held at the Sanfilippo Estate in Barrington, Illinois and drew hundreds of friends, colleagues and fans -- and the lines distinguishing fan from friend from colleague were virtually nonexistent -- from all over the country. Peter Straub, Neil Gaiman...et al.

I was asked to adapt one of Gene's stories for performance by a theater company, Terra Mysterium.

Here are just a few pictures from the day.

Jody Lynn Nye toasting Gene...

Gene on the Merry-Go-Round...

Gene on the Merry-Go-Round... Yes, there was a carousel in the banquet hall...

Yes, there was a carousel in the banquet hall...

Saturday, February 25, 2012

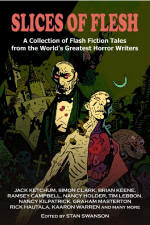

New Anthology: SLICES OF FLESH

I just received my .pdf proof-copy of "Slices of Flesh," a collection of horror flash fiction published by Dark Moon Books. "Slices..." is scheduled for launch at the World Horror Convention, March 29th - April 1, 2012 in Salt Lake City. Cover art is by Mike Mignola (Hellboy) with Dave Stewart doing the color work.

I mention this not because I've got a story in it but because I want to pimp the thing to you. The net proceeds from "Slices of Flesh" will go to aid the Stephen and Tabitha King Foundation, Project Literacy and so forth. The main thrust of it is to help the more than 30 million functionally illiterate American adults to learn to read. You know? Make new readers, keep people from becoming Repu... Well, you know.

I'm also posting this information because I'm proud as hell to be nestled in the book with these people...

Linda Addison

Janice Gable Bashman

Erin Bender

Laura Benedict

Max Booth III

Chantal Boudreau

Kevin James Breaux

Jason V. Brock

Reesa Brown

Jennifer Brozek

Ramsey Campbell

Tom Cardamone

Stewart Carrick

Sierra Christman

Simon Clark

Sandy DeLuca

Christopher DiLeo

James Dorr

David Dunwoody

Ed Erdelac

J G Faherty

Charlie Fish

Fran Friel

Sephera Giron

Charles Gramlich

Amy Grech

Eric J. Guignard

Bryan Hall

Rick Hautala

David Hayes

Brad Hodson

Nancy Holder

Del Howison

Robert Jackson

Lee F Jordan

Paul Kane

Nate Kenyon

Jack Ketchum

Nancy Kilpatrick

C. W. LaSart

Tim Lebbon

Adrian Ludens

Graham Masterton

Araminta Star Matthews

Kevin McClintock

Joe McKinney

Michelle Mellon

Lori Michelle

William F Nolan

Marie O'Regan

Michael O’Neal

Monica O'Rourke

J F Palma

Susan Palwick

J R Parks

R. B. Payne

Anne Petty

Aaron Polson

Lon Prater

Timothy Remp

Roy Robbins

Jacob Ruby

Lawrence Santoro

J W Schnarr

M R Sellars

Lorelei Shannon

Jeremy Shipp

Lance Shoeman

Wayne Simmons

Marge Simon

Douglas Smith

D L Snell

Simon Strantzas

Stan Swanson

David Tallerman

Richard Thomas

Peter Timony

Shelley Towne

Stephen Volk

Jeremy Wagner

Matthew Warner

Kaaron Warren

Lawrence Watt-Evans

Fred Wiehe

Connie Wilson

Jennifer Word

Good company, yes? When you can, get this book. It's good reading and your money could help a few people make a better life for themselves and maybe, just maybe it will save the planet. Well...it might!

Friday, January 13, 2012

Tales to Terrify is now live...

Now I can talk.

Now I can talk.Beginning today, Friday the 13th, January, 2012, you'll be able to stop by at "Tales to Terrify" and listen to the best in English language horror and dark fantasy. I'll be the weekly host of the show, produced by the Hugo Award-winning StarShipSofa.

TTT wil feature new fiction, classic tales, tales from the recent past by masters of the form and by voices that might be new to you. We'll also have reviews, commentary and more. So...drop in some midnight -- or any time -- and listen.

If you don't know Marty Mundt who's story, CHAIR, kicks off the site, Marty's a Chicago author, one of the centerpieces of the old Twilight Tales group. CHAIR is typical of Marty's work, a funny, witty, disturbing little piece. This one Reminds me of Voltaire or Swift. But, no, no....it's Mundt.

Marty's new novel. "Animated Americans" was recently published by Creeping Hemlock Press and is available on Amazon, B&N and wherever fine electrons congregate. It's also in ink on paper at those same sites.

Marty's new novel. "Animated Americans" was recently published by Creeping Hemlock Press and is available on Amazon, B&N and wherever fine electrons congregate. It's also in ink on paper at those same sites.Now go. Listen.

We're at http://talestoterrify.com/

Oh...the cover art for this month is by Michael Brack (http://michael.brack.free.fr/)

Comments to the site can be sent to TalesToTerrify@gmail.com Hope to hear from you.

Thursday, January 05, 2012

Root Soup, Winter Soup at Tuesday Funk

"Tuesday Funk," is a year+ old writer's reading series. It happens every first Tuesday of every month at the Hopleaf Bar on Clark Street, Chicago. Writer Bill Shunn is the host.

This past Tuesday, December 3, 2012, I read my short story "Root Soup, Winter Soup," from DRINK FOR THE THIRST TO COME.

By the way, I wasn't nervous. I've got a permanent tremor of the paws.

I hope you'll enjoy it.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)