Hazel Hawthorne Werner...was the literary hostess, doyenne salon-keeper of Provincetown, Massachusetts, during the town's gathering years as America’s beaux-arts colony extra ordinaire.

Hazel Hawthorne Werner...was the literary hostess, doyenne salon-keeper of Provincetown, Massachusetts, during the town's gathering years as America’s beaux-arts colony extra ordinaire.During the 20s, 30s, 40s Hazel also kept a salon in Greenwich Village.

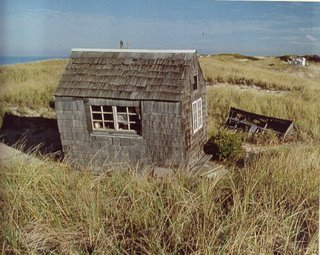

Edmund Wilson, E.E. Cummings, (before he lost his upper case), Eugene O'Neill -- the literary mob we kids of the 40s were raised on -- all hung out with her and her husband, Morrie Werner (editor, writer, drunk and P.T. Barnum biographer), in the Village then followed them up to P'Town on the Cape to hang with them on the dunesey sand. Hazel rented O'Neill the shack on the dunes in which he lived when he was writing his early plays. She rented, then gave it to him, kept him up and working, didn't let him slip into the booze and end-of-life drama he was writing himself into at the time. Hell, the "Sea Plays" were all written in Hazel and Morrie's shack on the beach and were first performed in a little potting shed down off Commonwealth Street (I think it was off Commonwealth -- it 's been a while since I've been there) before the plays went to New York and that city's "Provincetown Playhouse."

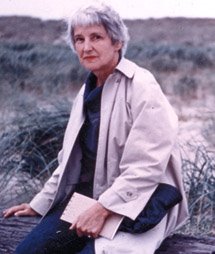

I knew Hazel when I lived in P'Town, 1970-71. She was lean, straight, and palsied, her voice, thin, reedy, and cut-glass proper. But despite seeming infirmity, Hazel, using no authority but strength of character, kept the Northeastern American literary establishment proper...not on-track artistically (she didn't seem to care about that), but she kept it, at least, minding its table manners through the 70s. She did, indeed. I watched.

I was married to a woman named Ernestine Worrall at the time. She and I attended a political meeting on behalf of George McGovern and a local candidate for the House of Representatives, Gerry Studds, in a church basement in P'Town.

Before coming up to P’town to work on a few projects, I had spoken passionately back home in Philadelphia on behalf of McGovern and of my ongoing dedication to that race. And at the meeting in Massachusetts, I committed my wife, talents and sacred hours to working not only for the McGovern presidency but for Mr. Studds election. It was the right thing to do...

A chum of ours, the just-down-from-Harvard editor of the Provincetown weekly paper (whenever you find yourself suddenly in a small town -- get to know the local editor!), rose, too, in personal defense of the Democratic Party and of George McGovern; he spoke of Richard Nixon’s perfidy and the ineffectiveness of the incumbent House Member from the Cape. We all filled with the rightness of our cause, the new rising of the young. Yada, yada.

Though it all, Norman Mailer bullied, railed, raged, threatened and called down the wrath of celebrity upon any who disagreed...

Without standing, with barely a look, a whip-thin, horsey, elegant old woman spoke. Pale, in a flowered dress, white socks rolled over sneakers, her voice ululating like a 78 Victrola on a bad road, her head quivering when she spoke. She froze Norman, all of us...

"Oh Norman, do sit down, for heaven's sake! You're behaving like a very bad boy!"

He did. Such was her authority.

That cut through the crap, the blowhardery. In 3 minutes, she'd focused the chatter and formed the kernel of a group to support Studds’ candidacy and, almost incidentally, to help McGovern.

If Senator McGovern can’t take Massachusetts without our help, she thought aloud, we can forget him, period.

Simple. That was that.

Hazel was the great-great-something-granddaughter of Nathaniel Hawthorne. The which did not impress her, in particular (she wasn't easily impressed). Her fetchin’s did, however, impart to her an impeccable authority as a New Englander. At least to other New Englanders. That sort of thing is important there. If you arrived at 15 and lived to be 85, you were still referred to as "the new fellah," to the natives.

Maybe that's true everywhere...

Hazel and Morrie had split up years before. I have no idea why. Why do those things happen anywhere?

She lived in the converted garage near where their house once stood. Fire, I believe, had removed the place. That was out on Shankpainter Road. My memory wants it to have been there...such a grand name for a forested trail along the dunes.

(Edit: While my memory might have wanted her place to be on Shankpainter Road, it was actually on Howland Street. Ah well...)

Morrie kept their apartment in New York.

She stayed in P'Town until each year became too cold to have her, until the winds threatened to stop her in her tracks or rush her off her feet. Then she'd go spend a few months to the South, in brick, with Morrie on the Upper East Side.

In Spring, she'd be back on the dunes.

For whatever reason, Hazel adopted Ernie, me; took us under her wing for the year we lived there.

I had come, commissioned by the Annenberg Center in Philly, to write a play -- a musical comedy about the Black Death.

Really!

For this endeavor I was reasonably well-accepted into the Confraternity of P'Town artists. Most of the people Ernie and I hung with were Pulitzer winners, National Book awardees, such and the like. A good part of our social life consisted of going to readings, openings, showings, presentations, lectures, events... Like that.

Hazel was not part of it but seemed to hover, invisibly around it; a mentioned absence, a spoken-of non-presence, a noted vacancy.

When our laureate chums found that, in addition to the serious -- and understandable -- work of writing a funny play about the Bubonic Plague, I was also interested in -- and actually DID write -- science fiction and fantasy, there was much side-glancing, wide-eyeing, and staring... Uncomprehending squints, stares and slow turns of heads.

Norman and Beverly Mailer, whose children we used to babysit from time to time, seemed to get it, seemed to be okay with it.

Others, simply passed us by.

Hazel, it seems, came to our rescue. By inviting us to dinner, by attending a few events with us, with her as our "guest", she turned the questioning stares of the entire arts community.

I don't doubt that it was a conscious choice on her part, this small intervention. She never did like pomposity, disdained arrogance.

Maybe she liked that I didn't care if this group accepted me. I actually didn't. Not too much, anyway.

Perhaps she liked Ernie's bread or the fact that we used to sit and chat with her at her place Saturday mornings, coffee and oatmeal, steamy windows and foggy skies and rolling ocean beyond her trees and dunes. Maybe she liked our talk of city streets, of Philadelphia, of chums and villains. Maybe she liked that we had time to talk about things other than bookish things.

Maybe she liked science fiction and fantasy.

Whatever it was, I liked her and so did Ernie. I got over her being the great great-grand-something-daughter of Nathaniel Hawthorne.

Hazel seemed, at once, fragile and razor strong. As I mentioned, she was palsied. Her hands ran a constant round-and-round circle of tremors and quivers. Her head bobbed, her voice quavered. To watch her eat, pour a cup, water a plant, was painful. Once, early, I made the beginning of a move to help her pour from her coffee pot.

She looked.

That was enough. I relaxed, so did she.

Despite multi-planar shakes Hazel didn't spill a drop; each move of each hand somehow found its correspondent move on the other.

Not

a

drop

Not important, her acceptance of me, her by-her-acts defense of me, not important at all in the long run of anything, but it was typical of her. She placed her person and the tradition which she seemed, unconsciously, to represent, at the service of a person whom, for whatever reasons, she liked.

After her "acceptance," Stanley Kunitz and his lady-woman embraced us; Alan Duggan, almost always drunk but still writing god-wonderful poetry, seemed to forget that in addition to doing a comic play about the Black Death, I also wrote pulpy things. He began publicly sharing the16oz cans of Blatz he always carried in his parka pockets with me up on Commonwealth by the coffee shop. Jack and Wally Tworkov had us in and that was that...

That was then, the McGovern year in Provincetown. By accident, in April, 2000, I found that Hazel, doubtless edging toward a hundred, was still alive. Standing possibly, probably, with one foot in the shadow of the 19th century, another in the 21st. She was then the oldest resident of Cape Cod.

How amazing.

No comments:

Post a Comment